Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:18 — 18.8MB)

Because there are so many weird fish out there, I’ve narrowed this week’s episode down to weird BIG fish! We’ll cover the smaller ones another time. Thanks to Damian and Sam for suggestions this week!

A manta ray being interviewed by a diver:

A manta ray with white markings:

A mola mola, pancake of the sea, with a diver:

The flathead catfish head. So many teeth:

A Wels catfish with Jeremy Wade:

A couple of red cornetfish:

Howick Falls in South Africa. Put that on my endless list of places I want to visit:

Further reading:

Karl Shuker’s blog post about the black and white manta rays

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s another listener suggestion week! Recently, Damian sent a list of excellent topic suggestions, one of which was weirdest fish, and I am ALL OVER that! But because there are so many weird fish, I’m going to only look at weird humongous fish this time, including a mystery fish.

We’ll start with a fish that doesn’t actually look very fishlike. Rays are closely related to sharks but if you didn’t know what they were and saw one, you’d probably start to freak out and think you were seeing some kind of water alien or a sea monster. The ray has a broad, flattened body that extends on both sides into wings that it uses to fly through the water, so to speak. The wings are actually fins, although they don’t look like most fish fins. Like sharks, rays have no bones, only cartilage. Rays are so weird that I’m probably going to give them their own episode one day, but for now let’s just look at one, the manta ray.

There are two species of manta ray alive today. The reef manta can grow 18 feet from wingtip to wingtip, or 5.5 meters. Manta birostris is even bigger, up to 29 feet across, or 8.8 meters, which is why it’s called the giant manta ray. This is just colossally huge. I didn’t realize how big manta rays were until just now. Both species live in warm oceans throughout the world and both eat plankton, krill, and tiny fish. Sometimes the manta ray is called the devil fish because of its horns, which aren’t horns at all, of course. The two protuberances that stick forward at the manta ray’s front are actually fins that grow on either side of the rectangular mouth. These fins help direct plankton into the mouth. When the manta ray isn’t feeding, it can roll up these fins into points and close its mouth. Its eyes are on the sides of its head.

Manta rays are white underneath and black or dark brown on top. But there is a mystery associated with the giant manta ray, with reports of black and white striped rays dating back to at least 1923. In April of that year, naturalist William Beebe spotted a manta ray near the Galapagos Islands that had white wingtips and a pair of broad white stripes extending from the sides of the head halfway down the back. Beebe thought it might be a new species of manta ray. There are other reports of manta rays with white or grayish V-shaped markings on the back.

Better than that, in the last few decades divers and boaters started to get photographs and even video of these manta rays with white markings. These days, manta rays with white markings are known to be common, although for decades scientists thought all manta rays were unmarked dorsally, or on the back. Since the markings are unique to individuals, it makes it easy for researchers to track individuals they recognize. The manta ray also sometimes has black speckles or blotches on its belly.

But wait, there’s more! According to zoologist Karl Shuker, in 2014, researchers in Florida published a paper discussing the ability of manta rays to actually CHANGE COLOR in minutes when they want to. The color in question that it changes? Its white markings. The markings can be barely visible against its background color, and then will brighten considerably when other manta rays are around or when it’s feeding. I’ll put a link to Shuker’s blog post in the show notes, which contains an excerpt from the article, if you want to read it.

The reef manta mostly lives along coasts, especially around coral reefs, while the giant manta ray sometimes crosses open ocean. Researchers used to think it migrated, but new studies suggest most don’t travel all that far. It does dive deeply, though, sometimes as deep as 3,300 feet, or 1,000 meters.

Another fish with a mostly cartilaginous skeleton instead of bone are the various species of ocean sunfish. The largest is the mola mola, although the southern sunfish is about the same size. Both grow to about 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters, and they are really, really weird.

The ocean sunfish doesn’t look like a regular fish. It looks like the head of a fish that had something humongous bite off its tail end. It has one tall dorsal fin and one long anal fin, and a little short rounded tail fin that’s not much more than a fringe along its back end. The sunfish uses the tail fin as a rudder and progresses through the water by waving its dorsal and anal fins the same way manta rays swim with their pectoral fins. Pectoral fins are the ones on the sides, while the dorsal fin is the fin on a fish’s back and an anal fin is a fin right in front of a fish’s tail. Usually dorsal and anal fins are only used for stability in the water, not propulsion.

Because it’s almost round in shape and its body is flattened, it actually kind of looks like a pancake with fins. I would not want to eat it but a lot of people do, with the fish considered a delicacy in some cuisines. These days it’s a protected species in many areas, but it often gets caught in nets set for other fish. It also ends up eating plastic bags and other trash that float like jellyfish.

The mola mola lives mostly in warm oceans around the world, and it eats jellies, small fish, squid, crustaceans, plankton, and even some plants. It has a small round mouth that it can’t close and four teeth that are fused to form a sort of beak. It also has teeth in its throat, called pharyngeal teeth. Its skin is thick and rough like sandpaper. It likes to sun itself at the water’s surface, and it will float on its side like a massive fish pancake and let sea birds stand on it and pick parasites from its skin. Occasionally it will jump completely out of the water, called breaching, as far as ten feet high, or 3 meters. Since the mola mola is one of the world’s heaviest fish that isn’t actually a shark or ray, sometimes weighing over two tons, or 2,000 kg, you really don’t want to be in a boat near a breaching mola mola. If it lands in your boat, it could sink you, or just squash you as flat as a finch under a giant tortoise.

Some researchers think the mola mola’s internal organs contain a neurotoxin—not a surprise since it’s related to the pufferfish—but we don’t know a whole lot about it yet and other researchers say it’s not toxic at all. Until recently researchers thought it only ate jellyfish, but more recent studies show that jellies only make up a small part of its diet. It feeds near the surface at night, but during the day it dives deeply, warming up between dives by sunning itself at the surface. Instead of a swim bladder, it has a layer of a jelly-like substance under its skin that helps make it neutrally buoyant.

The mola mola looks like it has no tail because it actually has no tail. Its little tail fin is called a pseudotail, or false tail. At some point during its evolution it lost its real tail. As a result, it has fewer vertebrae than any other fish, only 16. It’s a slow and clumsy swimmer but its size means it doesn’t have many natural predators beyond orcas and large sharks. It can grind its teeth together to make a croaking sound when it’s in distress. It can also blink, unlike most fish, and can retract its eyes deeper into their sockets to protect them.

In 2017, a new species of sunfish was named, the hoodwinker sunfish, Mola tecta. It grows up to ten feet long, or 3 meters, and is smooth and silvery with speckles. It’s really pretty. It lives in the southern hemisphere and that is pretty much all we know about it so far.

From the gentle giants of the sea, the manta ray and the mola mola, let’s move on to a weird freshwater fish that’s a lot scarier-looking. A few years ago, the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga, which is an awesome place that is well worth a visit if you’re in the area, was contacted by a man whose dog had found and was chewing on a hideous fish head. It had a wide grinning mouth full of rows and rows of short sharp teeth. He wanted to know what it was, naturally, because while it looked like a catfish, he’d never seen one with teeth.

It turns out that the flathead catfish does have teeth, and that’s what his dog had found. It’s native to parts of the southeastern United States into northern Mexico, but has been introduced in other places as game fish and can become an invasive species. It can grow really big, with the longest specimen ever caught measuring almost six feet long, or 1.75 meters, and weighing just shy of 140 lbs, or 63.45 kg. It eats fish, insects, crustaceans, and pretty much anything else it can catch. It’s yellowish or even purplish in color. The weird thing is that all the descriptions I read of the flathead catfish mentioned how big it is and how people like to fish for it, and how it is supposed to be the best-tasting catfish, but they don’t mention its horrifying teeth! I was going by the picture posted by the Tennessee Aquarium, sent in by the guy whose dog found the ultimate chew toy. That picture made the teeth look vicious. But I found a description of the teeth finally that said they’re more like sandpaper to human hands if you hold the fish correctly, possibly because the teeth are packed so tightly. I don’t want to put my fingers in a fish’s mouth for any reason, teeth or no teeth.

Big as it is, the flathead isn’t the biggest catfish in the world. That would be the Wels catfish, a topic suggestion by Sam. Thank you, Sam! The first time I heard about the Wels catfish was from the show River Monsters, where the fisherman Jeremy Wade caught several. I hope everyone listening finds a special someone one day who looks at them the way Jeremy Wade looks at gigantic fish. I love that show. The Wels catfish is native to parts of Europe but like the flathead catfish, it’s been introduced as a game fish in other areas and has become an invasive species.

Like other catfish, the Wels has a skin with no scales, but instead is protected by a layer of slime that has antibacterial properties. This is true for the manta ray and the sunfish too, in fact. It also has barbels that give catfish the name catfish, since the barbels look a little like whiskers. The barbels act as feelers and contain chemical receptors that help the fish taste potential prey in the water.

The Wels catfish likes warm, slow-moving water and can grow up to 16 feet long, or 5 meters, although most are much smaller. It has lots and lots of small teeth but it generally swallows its prey whole, sucking it into its big mouth. It eats fish, crustaceans, insects, worms, and anything else it can catch, but bigger ones will eat frogs, rats, even ducks and other birds. On occasion a Wels will come out of the water to catch a bird on land, but this behavior seems to be from fish that have been introduced to rivers and lakes that aren’t in its native range. The wels is also rumored to drown people and even eat them. There are reports of Wels catfish grabbing anglers by the leg or arm and dragging them into the water.

The red cornetfish lives throughout the world in tropical oceans, although young fish may live in the mouths of rivers that connect with the sea. It’s a long, skinny fish that can grow up to six and a half feet long, or 2 meters, but barely weighs more than ten pounds, or 4.7 kilograms. It can be red, orange, brownish, or even yellowish, sometimes with white or dark stripes or blotches. There’s some evidence that it can actually change its color to match its background. It also has a row of bony plates along its back.

The red cornetfish eats small squid, shrimp, and fish, which it’s able to sneak up on because it’s so incredibly thin. Basically, if it’s swimming straight toward you, all you see is a dot with two bulges for eyes. It also sneaks up on prey by hiding behind harmless fish that are fatter than it is, which is every fish.

The red cornetfish is related to pipefish and seahorses, and like those fish it has a long, pipe-like snout with a tiny mouth at the end that gives it its other common name, flutemouth. Its teeth are also tiny. At the end of its tail, a whip-like filament grows past the tail fin that extends the lateral line, which is a row of sensory cells that helps a fish detect the movements of other fish in the water.

Finally, let’s finish up with a mystery fish from South Africa. It’s called the inkanyamba and is supposed to be some twenty feet long, or six meters. It lives in lakes and near waterfalls and is generally supposed to look like a snake or eel with a horselike head.

The inkanyamba seems to be associated with storms and other severe weather, an association that goes back untold centuries to cave paintings of what are known as rain animals. So it could be that the inkanyamba is like the thunderbird, a creature of spiritual belief rather than a physical one. Groups such as the Xhosa and the Zulu believe that Inkanyamba is a giant winged snake that appears as a tornado as he flies around looking for his mate, who lives in a lake. Houses with metal roofs that aren’t painted are in danger from Inkanyamba since he might mistake the roof for water.

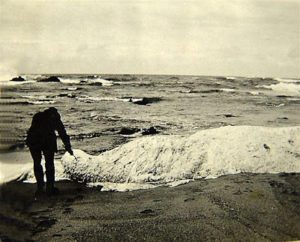

Then again, there are sightings. In 1962 a park ranger saw an eel-like or snake-like creature on a sand bank along the Umgeni River, which slithered into the water as he approached. Another witness sighted the monster twice near Howick Falls in 1971 and 1981. He said it was thirty feet long with a crest along its neck. The waterfall known in English as Howick Falls in South Africa is sacred to the Zulu, who believe it’s the home of Inkanyamba. It’s 310 feet high, or 95 meters, and is situated on the Umgeni River. The only people who are traditionally allowed to approach the pool at the base of the falls, or who can safely approach it, are sangomas, or traditional healers.

One suggestion is that the inkanyamba is a giant mottled eel, which has fins that run all around the tail like a crest. But it only grows to about six and a half feet long at most, or 2 meters. This is pretty big, but not anywhere near twenty or thirty feet. It eats fish, frogs, crustaceans, and other small animals, and isn’t dangerous to humans. It’s nocturnal, spends most of its time at the bottom of the lakebed or riverbed, and migrates from fresh water into the ocean to spawn and lay eggs. You may remember this from episode 49, which goes into the complicated details about eel migration.

I’m not convinced that Inkanyamba is an eel, even a big one. I think it’s more a creature of legend. If you’re lucky enough to visit Howick Falls, don’t get too close to the water, out of respect for a sacred place and just in case there’s something there that could eat you up.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!