Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:52 — 16.0MB)

This week we’re going to find out some surprising possible inspirations for the qilin, sometimes called the kirin or the Chinese unicorn, and the phoenix! Strap in, kids. We’re going to do history!

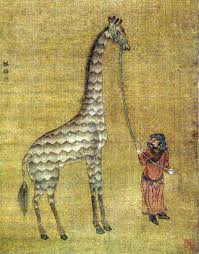

A qilin:

A giraffe:

My beautiful art of tsaidamotherium, both subspecies, with their weird horns:

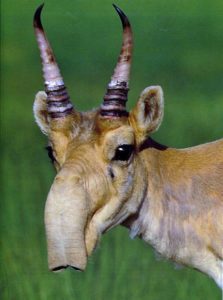

A saiga antelope

A takin:

A bird of paradise:

Another bird of paradise:

Further reading:

Dale Drinnon’s Frontiers of Zoology about the qilin

An online Bestiary. This is where I got the quotes from Herodotus.

The Book of Beasts, trans. T.H. White

The Lungfish, The Dodo and the Unicorn by Willy Ley

Extraordinary Animals Revisited by Karl P.N. Shuker

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about two animals that most people consider mythological—but they might be based on real animals that are as extraordinary as the folktales surrounding them.

The first is the qilin, also called the kirin or some other close variation. These days it’s usually depicted with a pair of antlers like a deer, but in older legends and artwork it often only had one horn, so is sometimes called the Chinese unicorn. It can resemble a dragon with cloven hooves, or a bull-like or deer-like animal with scales or a scaly pattern on its body. In Japan it’s usually depicted with one horn that curves backwards from its forehead.

The qilin legend is thousands of years old, with the first references dating back to the 5th century BCE. It has traditionally been considered a gentle animal whose appearance foretold the birth or death of a great ruler, or if it appeared to a ruler, it foretold a long, peaceful reign. Supposedly it first appeared to the Emperor Fu Hsi 5000 years ago as he walked along the banks of the Yellow River. A single-horned animal emerged from the water and walked so daintily that its cloven hooves didn’t leave prints in the mud. A scroll on its back was miraculously not wet, and when Fu Hsi unrolled the scroll he saw a map of his kingdom and written characters that taught him written language.

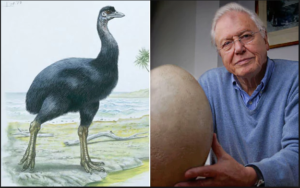

In 1414, explorer Zheng He brought a giraffe to China for the first time and presented it to the emperor as a qilin. The emperor wasn’t fooled, but it was a good PR move to treat the animal as a qilin. But the qilin was never depicted with a long neck before then, and even after, long-necked qilins were rare in art and sculpture. On the other hand, the Japanese word for giraffe is kirin, so there was some overlap.

The qilin was supposed to be solitary and lived high in the mountains and in deep forests. It ate plants and was described in various ways, as having a deer’s body and a lion’s head, or a horse’s body with a dragon’s head, or some other combination. It always had cloven hooves.

In 398 BCE, so more than 2,400 years ago, Greek historian Ctesias wrote a book about India, including the animals found in that land. Ctesias had never actually visited India, although he had traveled to a lot of other countries. This is what he wrote about the animal we now know as the unicorn: “There are in India certain wild asses which are as large as horses, and larger. Their bodies are white, their heads dark red, and their eyes dark blue. They have a horn on the forehead which is about a foot and a half in length.” Then he talks about the horn for a few more sentences, especially its supposed ability to cure diseases and neutralize poisons. If you’re interested in this aspect of the unicorn legend, I go over it at length in episode five, about the unicorn.

Most researchers think Ctesias was talking about the rhinoceros. But maybe he was referring to another animal, one that possibly contributed to both the unicorn legend and also to the legend of the qilin.

Tsaidamotherium was a bovid that lived during the late Miocene, around half a million years ago. Its fossils have been found in Northwestern China. It was probably most closely related to the musk ox and was adapted for life in cold mountainous regions. It had a high nasal cavity, which would have helped warm air before it reached the lungs. Other bovids found in cold areas tend to have similar structures. The Saiga antelope has a bulbous-looking face due to its large nasal passages, as does the takin, both of which also live in and around the Himalayas. But both the saiga and the takin have a pair of clearly separated horns. The saiga’s horns are long and look like typical antelope horns, while the takin’s horns resemble those of a musk ox, curving to the sides in a sort of U shape.

The really striking thing about Tsaidamotherium is its horns, and no animal living today has horns even slightly like it. It had a pair, but only the right horn grew large. The left one was much smaller, so that from a distance it looked like it only had one large horn on its head. These are not slender unicorn horns, though. They’re not even bull-like cow horns. There are actually two species of Tsaidamotherium that we know of, and they had differently shaped horns. T. hedini had thick horns that grew upward from the head like cones. The other, T. brevirostrum, with fossilized remains only described in 2013, had the same mismatched horns but both were short and squat and probably bent forward. I’ll put a couple of drawings in the show notes to give you an idea.

There are hints that Tsaidamotherium may have survived well into the modern era, probably in isolated pockets in the Himalayan Mountains. Until the mid-19th century there were reports of animals matching T. hedini’s description in Tibet, although even there it was considered rare to the point of near-legend. The first fossilized remains of Tsaidamotherium weren’t discovered until the early 20th century, in 1932. One interesting note is that the larger horn of T. hedini would probably have resembled the conical Yeti skullcaps sometimes found in monasteries in the Himalayas, although that’s probably a coincidence.

The Tsaidamotherium as Qilin is a theory put forth by Dale Drinnon, and I’ll link to the relevant post in the show notes if you want to read more.

Like the unicorn legend, which in one form or another has spread throughout much of the world, the phoenix has a long and complicated history. The modern story is still very close to what people believed in the middle ages and even before. It’s a mythical bird that every so often, usually every 500 years, would burst into flame, burn to ashes, and be reborn from those ashes into a new phoenix. There is only ever one phoenix. It’s usually depicted as eagle-like but not an eagle, and is usually red or gold.

Medieval writers loved the phoenix, because its cycle of rebirth from its own dead body practically wrote itself as a strong allegory to the Christian idea of redemption and the resurrection of Jesus Christ. In T.H. White’s translation of a 12th century bestiary, The Book of Beasts, the phoenix was supposed to live in Arabia and its big event is described like this:

“When it notices that it is growing old, it builds itself a funeral pyre, after collecting some spice branches, and on this, turning its body toward the rays of the sun and flapping its wings, it sets fire to itself of its own accord until it burns itself up. Then verily, on the ninth day afterward, it rises from its own ashes!”

After drawing the parallel with Christian symbolism, the book repeats itself with more detail, “it makes a coffin for itself of frankincense and myrrh and other spices, into which, its life being over, it enters and dies. From the liquid of its body a worm now emerges, and this gradually grows to maturity, until, in the appointed cycle of time, the Phoenix itself assumes the oarage of its wings, and there it is again in its previous species and form!”

Note that the second version of the story doesn’t mention fire. Instead of a fire, the phoenix builds itself a coffin from spices and dies inside it. Frankincense and myrrh are both plant resins used to make perfume and incense, by the way.

All this is interesting, but is the phoenix based on a real bird? People have been trying to figure that out for centuries. The problem is that the story is so old, so widespread, and so entrenched in popular culture that it’s hard to know what details point to real birds and what details are pure human imagination.

Some researchers even suggest that the phoenix might be based not on a bird at all, but a palm tree. In Greek the word phoenix also means palm tree. There are a lot of phoenix palms, including the kind that produce dates, and dates are delicious, so the tree may have been given a special status by associating it with the phoenix story. In ancient Egypt the symbol for the word benu was a stork-like bird that represented the sun but could also indicate a palm tree.

The word Phoeniceus was once a term for the color purple, so T.H. White thought the phoenix might be based on the purple heron, which he also thought might be the bird the Egyptians called benu. He suggested its rebirth story came about from its connection with the sun, which can be said to die every night and be reborn every morning.

Back in the 5th century BCE, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote about the phoenix in Egypt. He said, “The plumage is partly red, partly golden, while the general make and size are almost exactly that of the eagle. They tell a story of what this bird does, which does not seem to me to be credible: that he comes all the way from Arabia, and brings the parent bird, all plastered over with myrrh, to the temple of the Sun, and there buries the body. In order to bring him, they say, he first forms a ball of myrrh as big as he finds that he can carry; then he hollows out the ball, and puts his parent inside, after which he covers over the opening with fresh myrrh, and the ball is then exactly the same weight as the first; so he brings it to Egypt, plastered over as I have said, and deposits it in the temple of the Sun.”

This just sounds like a weird version of the phoenix story, about the phoenix making its own coffin out of myrrh and other spices. But there may be some strange truths hidden in the middle of this story and the others. It’s about the bird of paradise.

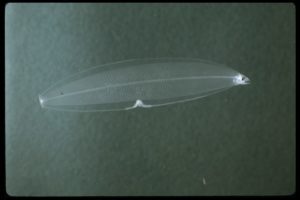

The bird of paradise is a real bird—or, rather, 42 species of real bird. You can go look them today in zoos and in their native homes in eastern Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea. They’re actually related to crows, although not closely, but they don’t look a thing like crows. Where crows are somber goth birds, the various birds of paradise are glorious in their coloring and plumage. Males of many species grow cascades of brightly-colored feathers during breeding season, which they display for the females in mating dances.

It was once thought that birds of paradise were unknown outside their home range until the early 16th century, when Magellan’s fleet limped back to Spain with a lot of exotic items, including the skins of some birds of paradise. The skins were apparently complete, except that they had no legs and appeared never to have had legs. Since almost nothing was known of the birds, people assumed they were so beautifully adapted to the air that they didn’t need legs, that the birds never landed.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that scientists actually saw living birds of paradise, complete with feet. It turns out that the natives of New Guinea were masters of preparing bird skins, removing the feathered skins from the body so skillfully that the bird appeared intact even though the legs had been removed.

Not only that, Australian researchers discovered during in-depth 1957 study of the bird of paradise skin trade, the natives of the region had been preparing birds for a long, long, long time—as far back as 1000 BCE. And they’d been trading them with seafarers who visited their islands long before Magellan was even born. The skins were prized for their beauty and transported all over, including to Phoenicia, a country famous for its purple dye. This is all starting to come together, isn’t it?

But it gets better. The bird of paradise skins were delicate, naturally, as were the long plumes still attached to the skins. To preserve them during voyages, they were packaged by the New Guinea natives like this: each skin was carefully wrapped in myrrh to make an egg-shaped parcel, and this was put in a larger parcel padded with burnt banana leaves.

Aromatic ashes containing an egg-shaped coffin made of myrrh, in which is the body of a glorious unknown bird? That sounds like a phoenix to me.

Like so many other legends, the phoenix is far more than just its original inspiration. Many birds probably inspired details of the story, just as many animals probably inspired stories of the qilin. Human imagination did the rest.

The legend of the phoenix and that of the qilin tell us as much about the people who have shared their stories for millennia than they tell us about any bird or animal. Humans are storytellers, no matter what culture and no matter how far back you look. After thousands of years, we’re still talking about the phoenix and the qilin, and we’ll continue to talk about them for thousands of years more. That’s an immortality worthy of the phoenix itself.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!