Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 24:42 — 25.1MB)

Subscribe: | More

Let’s learn about some weird insects this week! Thanks to Llewelly for suggesting army ants!

Further reading:

If you’re interested in the magazine Flying Snake, I recommend it! You can order online or print issues by emailing the editor, Richard Muirhead, at the address on the website, and there’s a collection of the first five issues on Amazon here (in the U.S.) or here (UK)!

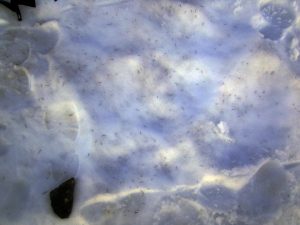

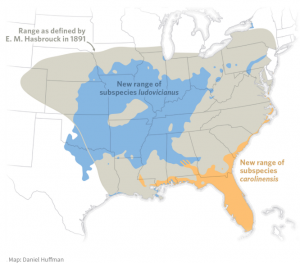

The magnificent, tiny ice worm! The dark speckles in the snow (left) are dozens of ice worms, and the ones on the right are shown next to a penny for scale. Teeny!

ARMY ANTS! WATCH OUT. These are soldier ants from various species:

The Appalachian tiger swallowtail (dark version of the female on the right):

Tiger swallowtails compared:

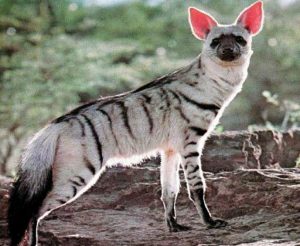

The giant whip scorpion. Not baby:

Jerusalem cricket. Also not baby but more baby than whip scorpion:

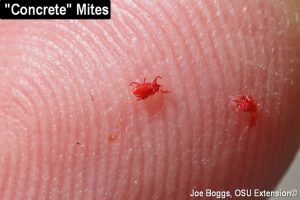

PEOPLE. GET THOSE HORRIBLE THINGS OFF YOUR HANDS.

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to talk about a number of strange and interesting invertebrates as part of Invertebrate August. Thanks to Llewelly for a great suggestion, and we also have a mystery invertebrate that I learned about from the awesome magazine Flying Snake. Flying Snake is a small UK magazine about strange animals and weird things that happen around the world. It’s a lot of fun and I’ll put a link in the show notes if you want to learn more about it. It’s been published for years and years but I only just learned about it a few months ago, and promptly ordered paper copies of all the issues, but they’re also available online and the first five issues are collected into a book.

So, let’s start with an invertebrate I only just learned about, and which I was so fascinated by I wanted to tell you all about it immediately! It’s called the ice worm, and it’s so weird that it sounds like something totally made up! But not only is it real, there are at least 77 species that live in northern North America, specifically parts of Alaska, Washington state, Oregon, and British Columbia.

The ice worm is related to the earthworm, and in fact it looks like a dark-colored, tiny earthworm if you look closely. It’s usually black or dark brown. It likes the cold—in fact, it requires a temperature of around 32 degrees Fahrenheit, or zero Celsius, to survive. You know, freezing. But the ice worm doesn’t freeze. In fact, if it gets much warmer than freezing, it will die. Some species live in snow and among the gravel in streambeds, and some actually live in glaciers. Ice worms can survive and thrive in such cold conditions because their body contains proteins that act as a natural antifreeze. It navigates through densely packed ice crystals with the help of tiny bristles called setae [see-tee] that help it grip the crystals. Earthworms have setae too to help them move through soil.

During the day, the ice worm hides in snow or ice to avoid the sun, and comes to the surface from the late afternoon through morning. It will also come to the surface on cloudy or foggy days. It eats pollen that gets trapped in snow and algae that is specialized to live in snow and ice, as well as bacteria and other microscopic or nearly microscopic animals and plant material. In turn, lots of birds eat ice worms. Birds also occasionally carry ice worms from one glacier or mountaintop to another by accident, which is how ice worms have spread to different areas.

The glacier ice worm can grow to 15 mm long and is only half a mm thick, basically just a little thread of a worm. It only lives in glaciers. You’d think that in such an extreme environment there would only be small pockets of glacier ice worms, but researchers in 2002 estimated that the Suiattle [soo-attle] Glacier in Washington state contained 7 billion ice worms. That’s Billion with a B on one single glacier. Other ice worm species can grow longer than the glacier ice worm, including Harriman’s ice worm that can grow nearly 2.5 inches long, or 6 cm, and is 2.5 mm thick.

There are tall tales about ice worms that can grow 50 feet long, or 15 meters, but those are just stories. An ice worm that big wouldn’t be able to find enough to eat.

Next, let’s talk about a type of ant. Llewelly suggested the army ant a long time ago, and recently I got an email from Ivy whose list of favorite animals includes the army ant!

The army ant lives in parts of Africa, South America, and Asia, and although there are some 200 species in different subfamilies, recent research suggests that many of them are descended from the same species that lived in the supercontinent Gondwana more than 100 million years ago.

Army ants don’t dig permanent nests like other ants. Instead they make temporary camps, usually in a tree trunk or sometimes in a burrow the ants dig. But these camps aren’t anything like ordinary ant nests. Often they’re formed from the bodies of worker ants, who link their legs together to make a living wall. The walls form tubes that make up chambers and passages of the nest, and inside the nest the queen lays her eggs. There are also chambers where food is stored. But the nest isn’t permanent. At most, the army ant only stays in one place for a few weeks, after the larvae pupate. The colony feeds the food stores to the queen, who lays a new batch of eggs timed to hatch when the new ants emerge from their cocoons. At that point, the colony breaks camp and enters the nomadic phase of behavior until the newly hatched batch of larvae are ready to pupate.

What do they do with the larvae while they wander? Workers carry them around. As in other ant species and the honeybees we talked about recently, an army ant colony is divided into different types of ant. There’s a single queen ant, seasonally hatched males with wings who fly off as soon as they’re grown, and many worker ants. But army ants have another caste, the soldier ant. These are much larger than the worker ants and have big heads and strong, sharp mandibles. Some species of army ant forage primarily on the ground while some hunt through treetops and some underground, but they generally hunt in large, well-organized columns with soldier ants on the outside as guards. In many species, the worker ants are further divided into castes that are specialized for specific tasks.

The queen ant is an egg-laying machine. Queens of some species can lay up to 4 million eggs every month. The queen is wingless, but a new queen doesn’t need to leave the colony the way other ant species do. Instead, when new queens emerge from their cocoons as adults, the colony splits and two new colonies form from the old one, each with one of the new queens. Usually more than two queens hatch, but only two survive.

When males emerge from their cocoons, they immediately fly off and search for another colony. But a male can’t just land and mate with a queen. He has to get through her guards, and they decide whether they like him or not. If they find him adequate, they bite his wings off and bring him to the queen. After he mates, he dies. This sounds like the plot of a weird science fiction novel from the 1960s. If a colony’s queen dies, the worker ants may join another colony.

Let’s talk specifically about the Dorylus genus of army ants for a few minutes, which live in Africa and Asia. Dorylus army ants live in simply enormous colonies. When the colony goes foraging, there may be 15 million ants marching in a dense column, and they can eat half a million animals every single day.

That’s why the army ant is so feared. The column of ants is made up of worker ants in the middle with the much larger soldier ants along the edges. The columns don’t move very quickly, but the ants attack, kill, and eat any living animal they encounter that can’t run away. This includes insects, spiders, scorpions, and lots of worms, but also eggs and baby birds, other baby animals, frogs and toads, and even larger animals. What isn’t eaten on the spot is carried back to the camp to feed larvae and the queen.

Army ants are also beneficial to the ecosystem and to humans specifically in many ways. A column of army ants that marches through a village will eat so many insects that they act like a really high quality exterminating service for homes and gardens. They also scare insects and other animals that flee from the ant columns, and a lot of animals benefit from the general chaos. Birds of many species will follow army ants in flocks, grabbing insects as they flee the ants. Some birds even make special calls to alert others that army ants are on the move, so that everybody gets a chance for easy food. Even more animal species will follow the column to clean up what they leave behind, including partially eaten carcasses, animals that were killed but rejected as food, and even the feces of the birds that follow the ants.

And, of course, a lot of animals just eat the army ants. Chimpanzees make different types of tools to help them safely harvest army ants. Most commonly, a chimp will use a stick it’s modified to the right length and shape, referred to as an ant-dipping probe. It will put one end of the stick down in the column of army ants and wait until ants start climbing up the stick. When there are enough ants on the stick, it will remove the stick and eat the ants off of it. It’s an ant-kebob!

If you’re wondering why the chimps aren’t attacked by the ants, or why the ants don’t figure out they’re climbing a stick to nowhere, Dorylus army ants, like most army ant species, are all blind. They communicate by releasing pheromones, which are chemicals with specific signatures that other ants can sense, something like smells. Some species that mostly live above-ground have re-evolved sight to a limited degree.

The mandibles of Dorylus army ant soldiers are so strong, and the ant is so tenacious about holding on, that people in some East African tribes traditionally use them to stitch up wounds. The soldier ant is held so that it bites with one mandible on each side of a wound, holding the edges of skin together. Then the person severs the ant’s body from its head, killing it—but the jaws are so strong that they will continue to stay in place for several days while the wound heals.

In Central and South America, the army ant genus Eciton [ess-ih-tahn] is very similar to Dorylus. Some species can cross obstacles like streams by building a living bridge out of individuals to allow the rest of the column to cross.

Whew, okay, I should probably have made the army ant its own episode, because there’s so much cool research about it that I could just go on forever. But let’s move on to a much different insect next, a butterfly that lives in the eastern United States, especially in the Appalachian Mountains. This is the Appalachian tiger swallowtail, which has yellow wings with black stripes and a black border, and a black body. Some females have all-black wings with orange spots. When the genetic makeup of the butterfly was examined, it turns out that the species originated as a hybrid of the Eastern tiger swallowtail and the Canadian tiger swallowtail. This kind of hybridization is rare in the wild. The Appalachian tiger swallowtail lives in the mountains, usually in high elevations, and while its range overlaps with both parent species, it almost never hybridizes with either. It has inherited the Canadian butterfly’s tolerance for cold but is twice its size. Researchers estimate that the hybridization occurred around 100,000 years ago.

I learned that interesting fact about the Appalachian tiger swallowtails from the May 2018 Flying Snake issue, and let’s go ahead and learn about a mystery invertebrate I also read about in that issue of Flying Snake.

The mystery is from The Desert Magazine, which was published between 1937 and 1985. It was a monthly magazine that focused on the southwestern United States, with article titles like “Rock Hunter in the Sawange Range” and “Ghost City of the White Hills.” Both those headlines are from the January 1947 issue, which is also where the first mention of the Baby of the Desert shows up in the letters section. Flying Snake excerpts the relevant letters from that issue and a few later issues, but I got curious and found the originals online.

I’ll quote part of the original letter because it’s really weird and interesting:

“Gentlemen: Would like to ask if there is such a thing as a very poisonous desert resident called ‘Baby of the Desert,’ so named because of the resemblance of its face to that of a human baby. Whether this so-called ‘Baby of the Desert’ is supposed to be insect, reptile or rodent, I could not find out. …[I]t was considerably smaller than the Gila monster.”

The letter was signed William M. Weldon from South Pasadena, California.

The editor responded, “The question of the Baby of the Desert, Baby-face, or Niño de la Tierra, as it is variously called, came up for discussion on the Letters page of the magazine two years ago. A reader sent in a description of the fearsome beast as it had been pictured to him and asked for confirmation from someone who had seen it.”

Because of the mention of another letter asking about the Baby of the Desert, two years before, I went through the letters sections of all the 1945 issues to find the original. I couldn’t find it in 1945, but I did find a nice letter from James Mayberry in California, who found a desert tortoise with blue paint on its shell. He thought someone had brought the tortoise back from a visit to the desert. James named the tortoise Mojave but knew it needed to go home, so he sent it to the Desert Magazine. I’m delighted to say that the editor took it out to a lonely desert hill where there were other tortoises and let Mojave go. Tortoises live a long time so Mojave might still be stumping around out there, the blue paint on his shell faded in the sun.

Then I went back through the 1944 issues and found the letter in the July issue. It was from Albert Lloyd of Tulsa, Oklahoma, who wrote, “Perhaps some reader can supply authentic information about a small denizen of the deserts and mesas of the Southwest, which the Mexicans call Niño de la Tierra, or Child of the Earth. During four years of roaming around New Mexico and Arizona I was never fortunate enough to see one. But I have talked with several who claim to have seen it. They describe it as a doll-like animal, about three or four inches in length, walking on all fours, with head and face like that of an infant. They claim it will not attack you unless molested and that its bite is more deadly than a rattlesnake’s.”

The editor of the Desert Magazine suggested that the Baby of the Desert was an insect. “[I]t appears that the Baby-face is actually our old friend the yellow and black striped Jerusalem cricket or Sand-cricket, who is nocturnal and usually found under boards or stones.”

But responses in the letters section in following issues, February and April 1947, don’t agree. S.G. Chamberlin of San Fernando, California wrote, “Some years ago…we uncovered what we first thought to be a Jerusalem Cricket. The coloring was the same and it was a little more than two inches long. Later in the day a ranch hand brought us a Jerusalem Cricket and then we noticed quite a difference in the bodies and heads of the two insects. The round face of the first one did attract our attention although we didn’t think of a baby at the time. The ranch foreman placed them in different bottles to show them to a man in the Farm Bureau office who was versed in such things. He reported back that the first insect was called Vinegarones or Sun Spider and supposed to be harmless.

“At the ranch we were told that on the Mexican border there was a similar insect that is supposed to be poisonous.”

And Coila Harris of South Laguna, California wrote, “I was interested in the recent letters about ‘Baby Face.’ This is not the Jerusalem cricket or potato bug, as many believe, but could be mistaken for one of these insects. Baby-face lives down Mexico way. When we were living in El Paso, one of the weird looking bugs was found under our house. It had a body of a large Tarantula, the head was white as a bleached bone and looked like a bald headed baby, a dreadful thing. I was told at the time that Mexicans consider them so poisonous, that if bitten on the finger by one, they chop off the finger.”

Unfortunately for me, the second I saw the mention of a vinegarone, I had a good idea of what this animal might be. And I really don’t want to look at pictures of vinegaroons.

I do try very hard not to be biased against gross-looking insects, because for one thing, they aren’t hurting me and gross is in the eye of the beholder. One person’s “ooh gross” is the other person’s “Oh, that is so neat!” Spiders don’t bother me and as long as I don’t have to look closely at an invertebrate’s mouthparts and things, I’m usually okay. But I get a big case of the nopes when it comes to the vinegaroon.

The vinegaroon is an arachnid, related to spiders and scorpions. It sort of looks like a mixture of the two, although there are lots of species and they vary quite a lot. It’s also called the whip scorpion. The name vinegaroon comes from the acidic liquid it squirts from the base of its whip-like tail if it feels threatened, which smells like vinegar. It lives in tropical and subtropical parts of the Americas and Asia, with one species known from Africa. Most species prefer dark, humid areas and live in burrows in rotting wood or under rocks and leaf litter, but the giant whip scorpion lives in more arid areas in the southwestern United States and Mexico.

The giant whip scorpion grows to around 2.5 inches long, or 6 cm, not counting the long whip-like tail. Like all vinegaroons, it eats insects, slugs, and other small animals. But no one could look at it and think “baby.” It has big claw-like pedipalps in addition to six walking legs and a pair of front legs that are extremely long and thin, that it uses to feel around with. It has eyes—in fact, like spiders it has eight eyes—but it doesn’t see very well and mostly navigates by touch. It’s dark brown or black with some lighter brown markings on its abdomen.

The Jerusalem cricket looks superficially similar to the vinegaroon although it’s not an arachnid. It’s also not a cricket, and it doesn’t have anything to do with Jerusalem since it’s native to the western United States and Mexico. In fact, it’s related to the weta of New Zealand. It lives in the same sort of places that vinegaroons like, burrowing in moist soil and rotting wood, but it mostly eats decaying plant material although it will sometimes eat small insects. It can bite, although it’s not venomous or poisonous, but it can give off a horrible smell if it’s disturbed. It’s yellowish to dark reddish-brown with a black-striped abdomen and a rounded head. It also does not look anything like a baby.

BUT, while it’s known by a couple of Navajo names that translate to variations on “red skull bug,” in Spanish it’s called cara de niño, which means child’s face, or niño de la tierra.

So I think the Desert Magazine editor was right. The Baby of the Desert is the Jerusalem cricket. But I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if the Jerusalem cricket is sometimes confused with the giant whip scorpion. They’re both large nocturnal creatures with a similar body shape and coloring, that live in the same areas and occupy the same habitat. And they’re both horrifically creepy-looking. You know what? I bet you anything that “Baby of the Desert” and “baby-face” are ironic names. BAD BABY.

The Jerusalem cricket doesn’t have any kind of hearing organs akin to ears but it can sense vibrations. Instead of chirping, it drums its abdomen on the ground to attract a mate. This is what the drumming sounds like.

[Jerusalem cricket drumming]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!