Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:55 — 13.8MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

Thanks to Nicholas and Emma for their suggestions this week as we learn about some (nearly) indestructible animals!

Further listening:

Patreon episode about Metal Animals (unlocked, no login required)

Further reading:

Even a car can’t kill this beetle. Here’s why

The scaly-foot snail’s shell is made of actual iron – and it’s magnetic

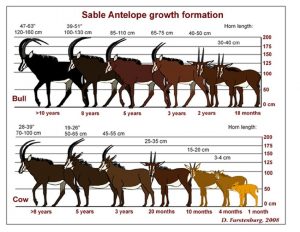

The scaly-foot gastropod (pictures from article linked above):

The diabolical ironclad beetle is virtually unsquishable:

Limpet shells:

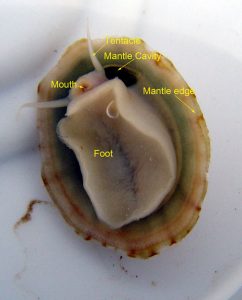

The business side of a limpet:

Highly magnified limpet teeth:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some indestructible animals, or at least animals that are incredibly tough. You may be surprised to learn that they’re all invertebrates. It’s a suggestion by Nicholas, and one of the animals Nicholas suggested was also suggested by Emma.

We’ll start with that one, the scaly-foot gastropod, a deep-sea snail. We actually covered this one a few years ago but only in a Patreon episode. I went ahead and unlocked that episode so that anyone can listen to it, since I haven’t done that in a while, so the first part of this episode will sound familiar if you just listened to that one.

The scaly-foot gastropod lives around three hydrothermal vents in the Indian Ocean, about 1 ¾ miles below the surface, or about 2,800 meters. The water around these vents, referred to as black smokers, can be more than 350 degrees Celsius. That’s 660 degrees F, if you even need to know that that’s too hot to live.

The scaly-foot gastropod was discovered in 2001 but not formally described until 2015. The color of its shell varies from almost black to golden to white, depending on which population it’s from, and it grows to almost 2 inches long, or nearly 5 cm. It doesn’t have eyes, and while it does have a small mouth, it doesn’t use it for eating. Instead, the snail contains symbiotic bacteria in a gland in its esophagus. The bacteria convert toxic hydrogen sulfide from the water around the hydrothermal vents into energy the snail uses to live. It’s a process called chemosynthesis. In return, the bacteria get a safe place to live.

The snail’s shell contains an outer layer made of iron sulfides. Not only that, the bottom of the snail’s foot is covered with sclerites, or spiky scales, that are also mineralized with iron sulfides. While the snail can’t pull itself entirely into its shell, if something attacks it, the bottom of its foot is heavily armored and its shell is similarly tough.

Researchers are studying the scaly-foot gastropod’s shell to possibly make a similar composite material for protective gear and other items. The inner layer of the shell is made of a type of calcium carbonate, common in mollusk shells and some corals. The middle layer of the shell is regular snail shell material, organic periostracum, [perry-OSS-trickum] which helps dissipate heat as well as pressure from squeezing attacks, like from crab claws. And the outer layer, of course, is iron sulfides like pyrite and greigite. Oh, and since greigite is magnetic, the snails stick to magnets.

Unfortunately, the scaly-foot gastropod is endangered due to deep-sea mining around its small, fragile habitat. Hopefully conservationists can get laws passed to protect the thermal vents and all the animals that live around them.

The scaly-foot gastropod is the only animal known that incorporates iron sulfide into its skeleton or exoskeleton, although our next indestructible animal, the diabolical ironclad beetle, has iron in its name.

The diabolical ironclad beetle lives in western North America, especially in dry areas. It grows up to an inch long, or 25 mm, and is a dull black or dark gray in color with bumps and ridges that make it look like a piece of tree bark. Since it lives on trees, that’s not a coincidence. It spends most of its time eating fungus that grows on and under tree bark.

Like a lot of beetles, it’s flattened in shape. This helps it slide under tree bark and helps it keep a low profile to avoid predators like birds and lizards. But if a predator does grab it and try to crunch it up to eat, the diabolical ironclad beetle is un-crunchable. Its exoskeleton is so tough that it can withstand being run over by a car. When researchers want to mount a dead beetle to display, they can’t just stick a pin through the exoskeleton. It bends pins, even strong steel ones. They have to get a tiny drill to make a hole in the exoskeleton first.

The beetle’s exoskeleton is so strong because of the way it’s constructed. In a late 2020 article in Nature, a team studying the beetle discovered that the exoskeleton is made up of multiple layers that fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. Each layer contains twisted fibers made of proteins that help distribute weight evenly across the beetle’s body and stop potential cracking. At the same time, the arrangement of the exoskeleton’s sections allows for enough give to make it just flexible enough to keep from cracking under extreme pressure. Of course, this means the beetle can’t fly because its wing covers can’t move, but if it falls from a tree it doesn’t need to worry about hurting itself.

Engineers are studying the beetle to see if they can adapt the same type of structures to make airplanes and cars safer.

Nicholas also suggested the limpet, another mollusk. It’s a type of snail but it doesn’t look like the scaly-foot gastropod or like most other snails. Its shell is shaped like a little cone with ridges that run from the cone’s tip to the bottom, sort of like a tiny ice-cream cone that you don’t want to eat. There are lots of species and while a few live in fresh water, most live in the ocean. The limpets we’re talking about today are those in the family Patellidae.

If you think about a typical snail, whose body is mostly protected by a shell and who moves around on a wide flat part of its body called a foot, you’ll understand how the limpet is a snail even though it looks so different superficially. The conical shell protects the body, and the limpet does indeed move around on a so-called foot, gliding along very slowly on a thin layer of mucus.

The limpet lives on rocks in the intertidal zone and is famous for being able to stick to a rock incredibly tightly. It has to be able to do so because otherwise it would get washed off its rock by waves, plus it needs to be safe when the tide is out and its rock is above water. The limpet makes a little dimple in the rock that exactly matches its shell, called a home scar, and as the tide goes out the limpet returns to its home scar, seals the edges of its shell tight to the rock, and waits for the water to return. It traps water inside its shell so its gills won’t dry out while it waits. If the rock is too hard for it to grind down to match its shell, it grinds the edges of its shell to match the rock. It makes its home scar by rubbing its shell against one spot in the rock until both are perfectly matched.

The limpet mostly eats algae. It has a tiny mouth above its foot and in the mouth is a teensy tongue-like structure called a radula, which is studded with very hard teeth. It uses the radula to rasp algae off of the rocks. Other snails do this too, but the limpet has much harder teeth than other snails. Much, much harder teeth. In fact, the teeth of some limpet species may be the hardest natural material ever studied.

The teeth are mostly chitin, a hard material that’s common in invertebrates, but the surface is coated with goethite [GO-thite] nanofibers. Goethite is a type of of iron, so while the limpet does have iron teeth, it still doesn’t topple the scaly-foot gastropod as the only animal known with iron in its skeleton. Not only does the goethite help make the teeth incredibly strong, which is good for an animal that is scraping those teeth over rocks constantly, the dense chitin fibers in the teeth make them resistant to cracking.

The limpet replaces its teeth all the time. They grow on a sort of conveyer belt and move forward until the teeth in front, at the business end of the radula, are ready to use. It takes about two days for a new tooth to fully form and move to the end of the radula, where it’s quickly worn down and drops off.

Meanwhile, even though the limpet’s shell doesn’t contain any iron, its shape and the limpet’s strong foot muscles mean that once a limpet is stuck to its rock, it’s incredibly hard to remove it. It just sits there being more or less impervious to predation. Humans eat them, although they have to be cooked thoroughly because they’re tough otherwise, naturally.

Finally, one animal that Nicholas suggested is probably the royalty of indestructible animals, the water bear or tardigrade. Because we talked about it recently, in episode 234, I won’t go over it again. I’ll just leave you with an interesting note that I missed when researching that episode.

In April of 2019, an Israeli spacecraft was launched that had dormant tardigrades onboard as part of an experiment about tardigrades in space. There were no people onboard, fortunately, because the craft actually crashed on the moon instead of landing properly. The ship was destroyed but the case where the tardigrades were stored appears to be intact.

It’s not exactly easy to run up to the moon and check on the tardigrades, so we don’t know if they survived the crash landing. Studies since then suggest they probably didn’t, but until we can actually land on the moon and send a rover or an astronaut out to check, we don’t know for sure. Tardigrades can survive incredibly cold, dry conditions while dormant. It’s not exactly the experiment researchers intended, but it’s definitely an interesting one.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes. There are links in the show notes to join our mailing list and to our merch store.

Thanks for listening!