Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:22 — 14.3MB)

It’s Halloween week! Join us this week for an episode about spooky, spooky owls…including the chickcharnie and the owlman.

I’ve unlocked a few Patreon episodes as a Halloween treat. Click through and you can listen on your browser:

And a reminder that my fantasy novel Skytown is available now in ebook and paperback. Buy many copies!

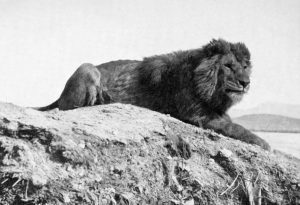

The Eurasian eagle owl will murder you without remorse and look fabulous doing it:

The Eastern screech owl is tiny but has a loud, creepy call:

The barn owl is sometimes called the ghost owl FOR OBVIOUS REASONS:

A great horned owl:

Further reading:

The Telltale Lilac Bush and Other West Virginia Ghost Tales by Ruth Ann Musick

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s finally Halloween week, my favorite week of the year! Let’s learn about another animal frequently associated with Halloween spookiness, the owl!

First, though, a reminder that if you want a Strange Animals sticker, always feel free to contact me and ask for one. You can email me at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com or contact me through social media. If you’ve got an extra dollar or two a month just lying around, you can support the podcast on Patreon and get access to twice-monthly bonus episodes. And if you want to read a fun book that actually has very little to do with animals, my novel Skytown is now out in both paperback and ebook. I’ll put a link in the show notes for both my book’s Goodreads page and to the Patreon page. Not everyone knows what Patreon is, so briefly, it’s just a site where you can set up recurring monthly donations and in return get patron rewards.

I have unlocked two more patreon bonus episodes for anyone to listen to. I’ll put a link to them in the show notes too. You can click on the links and listen via your browser, without needing a Patreon login.

Now, with housekeeping out of the way, on to the owl episode!

Like bats, owls are mostly nocturnal animals and that makes many people afraid of them. They also look kind of weird, can sound really creepy, and fly so silently that they’re like ghosts. But we’re going to start this week’s episode off with an owl-like mystery animal in a place you might not expect.

The Bahamas is a country made up of over 700 islands, many of them tiny, located roughly between the Florida peninsula and Cuba. These days it’s famous for sunny beaches and warm waters. Tourism is a big part of its economy and lots of people take cruises to the Bahamas. But between about 500 years ago and 200 years ago, the Bahamas was a terrible place. The native people of the area, called the Lucayan, were enslaved by the Spanish and forced to work on plantations under horrific conditions. Most of them died. The British took over the islands around the mid-17th century, bringing enslaved people from Africa to work the plantations. Also during this time, pirates treated the area as a haven, leading eventually to one really good Pirates of the Caribbean movie and a lot of terrible sequels, although this is perhaps a little off topic. In 1807 the British came to their senses and abolished the slave trade, although they didn’t actually abolish slavery until 1834. British ships sometimes attacked slave ships and rescued the captives on board. Many of the captive people were brought to the Bahamas, where they made new homes. Freed and escaped slaves made their way to the Bahamas too, where they could live in relative peace.

The largest of the islands that makes up the Bahamas is called Andros Island, although it’s technically a collection of three main islands and some smaller ones that are all quite close together, protected by a barrier reef. It’s the only island in the Bahamas with a freshwater river, and naturally there are many animals found on Andros Island that live nowhere else. There used to be even more native animals, before the forests of Andros were chopped down.

The island has many spooky stories, of course. Most places do, and the darker the history of a place, the more spooky stories it’s likely to have. For instance, it’s said that a fisherman named James was caught in a hurricane one night and never arrived home. His fiancée, a woman named Anna, spent every night walking along the beach and waving a lantern, hoping against hope that he was alive and would be able to find his way home when he saw her light. But he never came home, and eventually Anna was found on the beach one morning, dead of a broken heart. Then, a year after James’s disappearance, another storm blew up. The fishermen of the island sailed for home as fast as they could, but the night was dark, the waves were enormous, and the rain pelted down so hard they couldn’t tell which way they were sailing. Then one sailor noticed a small light waving in the distance. All the fishermen turned their boats in that direction, and they all managed to reach land safely. But they couldn’t figure out what the light was that they had seen…until the morning, when the storm had blown over. On the beach they found the wreckage of James’s boat, lost the year before and finally blown ashore…and they also found Anna’s lantern lying on the sand although she had been buried months before. Oh my gosh, that is spooky.

But the Andros Island story we’re interested in today is that of a creature called the chickcharney. It’s sort of a bird, sort of a goblin. It was supposed to be about three feet tall, or almost a meter, with big round eyes—possibly only one eye in the middle of its face. It was covered with hairy feathers and could turn its head almost all the way around. Some versions of the story say it had a long prehensile tail that it used to climb trees. It was supposed to live in the pine forests and make its nest in trees that were so close together that the branches touched near the top.

The chickcharney was mischievous and would sometimes play tricks on people, but if people treated it with respect and left it alone, they would have good luck. If they bothered it, not only would they have bad luck, sometimes the chickcharney would grab the person and twist their head around backwards. The best way to keep the chickcharney from bothering you was to carry brightly colored cloth or flowers when you went into the woods.

You may think that the story of the chickcharney is a lot less believable than the one about James and Anna. But as it happens, Andros Island used to be home to a flightless owl that sounds a lot like the chickcharney.

The Andros Island barn owl stood over three feet tall, or about a meter, with long legs, and lived in the pine forests. It was a burrowing owl that nested in holes beneath the trees, but we don’t know much about it since it’s extinct. It probably went extinct in the 16th century when the pine forests on Andros Island were felled, but people still report seeing the chickcharney. So while it’s a slim chance, maybe a small population of the owl is still hanging on.

Another owl-like cryptid is called the owlman. Supposedly, in April of 1976 two sisters saw a huge winged creature hovering over a church tower during a family holiday in Cornwall, England. In July of that same year, two other girls who were camping near the church heard and saw a huge owl. They said it was the size of a grown man, had red eyes and pointed ears, and black claws. It hissed at them and flew straight up into the air. Other people reported seeing the owlman too.

The problem with this story is that it was initially reported and investigated by a man named Doc Shiels, who has been associated with hoaxes in the past. But if the owlman sightings are real, could the witnesses be seeing an actual owl?

One of the biggest owls alive today is the great grey owl, which lives throughout northern Eurasia and in parts of Canada and the northwestern United States. Its body is nearly three feet long, or 84 cm, and its wingspan can be up to five feet across, or 1.5 meters. It’s brown and grey with yellow eyes, and it mostly eats small rodents. It has incredible hearing and can hear animals moving around under up to two feet of snow, which it then dives into to catch its prey.

But the great grey owl doesn’t live in England, and it doesn’t really fit the sightings of owlman. The Eurasian eagle-owl does, and while it also doesn’t typically live in England, up to 40 pairs are estimated to live in the British Isles and it’s common throughout much of Eurasia.

The Eurasian eagle-owl has a shorter body than the great grey owl, but its wingspan is broader. Females are larger than males, so a big female might have a wingspan up to 6 feet 2 inches, or 1.9 meters. Females also tend to have darker plumage than males. The Eurasian eagle-owl has ear tufts and its eyes are orange or red-orange. It eats small mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, even large insects.

Like many owls, the Eurasian eagle owl will hiss when it’s disturbed. It will also fly during the day when it’s been disturbed, although it will sometimes hunt before it’s fully dark.

But could someone mistake an owl for a human-sized creature? No matter how big their wings are, owls just aren’t that big.

Then again, most people aren’t very familiar with owls. I’m an avid birder and I don’t see owls very often, so the average person who isn’t into birdwatching may never have seen an owl in person before. Owls look even bigger than you think they would because of how enormously fluffy their feathers are, and if they’re disturbed they may ruffle their feathers out to look even bigger. Their legs are much longer than you’d think too. Add in someone being startled and potentially really scared by a sudden owl, and possible poor light conditions, and you have a recipe for owlman reports.

Even if owlman is probably just a giant owl, owls in general are just kind of creepy. Creepy-cute, but definitely on the spooky end of the animal spectrum. And all those odds and ends of weird facts you know about owls? They’re probably true.

For instance, owls really can turn their heads around backwards and even farther, as much as 270 degrees. Owls have 14 neck vertebrae, twice as many as humans and most other mammals have, and they have other adaptations that allow them to turn their heads that far without injury. The reason owls need to be able to turn their heads so far is because they can’t move their eyes. Owl eyes are fixed in their sockets so they can only look straight ahead from wherever their head is pointing. This is actually the case for most birds.

Owls are nocturnal and can see extremely well even in low light. Owls that mostly hunt in darkness have black eyes, while owls that usually hunt at dawn or dusk have yellow or orange eyes. Most owls have good hearing too. The reason many owls have that circle of feathers around their eyes, called a facial disc, is to help focus the owl’s hearing. The owl can adjust the angle of the feathers in its facial disc to focus sounds. Not only that, some owls have asymmetrical ear cavities, which makes it easier for them to pinpoint the source of sounds. The ear tufts some owls have on their heads are not actually ears or anywhere near the ear cavities. They’re just decorations.

Owl feathers are shaped so that the owl can fly silently, not only softening the edges of the feathers so sound is reduced, but lowering the frequencies of the sounds produced by the feathers so that it’s below the prey’s hearing spectrum, while the owl can hear itself and other owls flying just fine. Researchers are studying owl feathers to help design quieter airplane wings, wind turbines, and other machines.

Most bird feathers are somewhat waterproof because when a bird preens, it spreads oil over the feathers. Owls don’t do this, which means owls can’t hunt in wet weather.

An owl swallows its prey whole. Teeth, claws, some bones, hair, and feathers can’t be digested, so instead of passing through the digestive system, these indigestible pieces are compacted into pellets in the gizzard and regurgitated by the owl before it eats its next meal. Researchers study owl pellets to determine what an owl is eating. Some other birds of prey make pellets too, including hawks and eagles.

There are a lot of superstitions about owls, just as there are about bats. Some cultures believe that an owl calling around a home means someone who lives there is going to die, but some cultures consider owls lucky. Owls are also known for their wisdom, and I do not know where this comes from because they’re no smarter or dumber than any other bird. Actually, I do know where this comes from. The owl was associated with the Greek goddess of wisdom, Athena.

If you wonder why anyone would think an owl’s call is a bad omen, you may not have heard an owl call. Sure, some owls make jolly little hoot-hoot sounds. But some sound like this:

[screech owl call]

That’s an eastern screech owl, and I recorded it myself in my own driveway a few weeks ago. It sounds like a ghost. A lot of owls sound like ghosts. I mean, I’ve never actually heard a ghost. I’m just making an assumption that they sound scary. Maybe people who hear scary owl calls didn’t know what was making the sound, and assumed they were made by ghosts.

Some people even call barn owls ghost owls. Some farmers in Florida and other areas have started putting up nest boxes to attract barn owls, because owls hunt rats that damage sugar cane and other crops. Putting up owl nest boxes is a lot less expensive and better for the environment than rat poison. The common barn owl lives throughout much of the world. It’s brown or gray on its back, white underneath, and with a white face and dark eyes. It’s a medium-sized owl with a wingspan of about three feet, or 95 cm. This is what it sounds like:

[barn owl call]

Let’s finish with a creepy little story I found in a book called The Telltale Lilac Bush by Ruth Ann Musick. It’s a collection of ghost tales from West Virginia, and Musick was a folklorist who collected the tales with the help of her students. I reread the book this week hoping to find mention of an owl to close out this episode. Instead, I found this. Listen and decide what you think really landed on this poor man’s back during his ride through the night. It’s a story called “A Ride with the Devil,” collected in 1955 and related to the student by his mother, as told to her by her mother.

“One dark evening, about one hundred years ago, my great-grandfather had a strange experience. He was riding his horse back from a small country store somewhere in Randolph County in the vicinity of Mill Creek. He heard something that sounded like a log chain falling from a tree, and then he felt the presence of something on the horse behind him.

“He was frightened half out of his wits, but he turned his head around to see what the thing was. First he saw long claws that were digging into the flesh on his shoulder. He thought that a bear had jumped behind him on his horse, but, turning his head farther around, he found himself staring straight into two fire-red eyes. The creature had hardly any nose, but there were two protruding objects on his head that looked like horns. He was face to face with Satan himself! He tried many times to shake him off his back. He pushed. He tried racing his horse to get rid of him. But all this did no good. Satan clung to his back with those razorlike claws through it all.

“As he came within sight of his home, a strange thing happened. To his utter surprise, the thing disappeared.

“Upon arriving home, he slowly walked into the house. His wife noticed his torn shirt and bleeding shoulder and was terrified.

“He told her the whole story, but asked her never to say anything about it to anyone. Then he said something else. He said, ‘I have just seen the devil, and it won’t be long now before he gets me.’

“Exactly three weeks from that chance meeting with the devil, Grandfather fell while repairing his tobacco shed and was killed almost instantly. His last word before he died was ‘Water!'”

On a possibly related note, this is what a great horned owl sounds like:

[great horned owl hoot]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!